We present a case study of the online education and public outreach (EPO) program of The Dark Energy Survey (DES). We believe DES EPO is unique at this scale in astronomy, as it evolved organically from scientists’ volunteerism. We find that DES EPO online products reach 2,500 social media users on average per post; 94% of these users are predisposed to science-related topics. We find projects which require scientist participation and collaboration support are most successful when they capitalize on participating scientists’ hobbies. Throughout the article, we present recommendations for others interested in facilitating EPO for large science collaborations.

Click here for the analysis article on the arXiv.

As a complement to the article above, we present additional information and analysis which provides context for the creation of the DES EPO program as a part of the DES collaboration and for programs in place before EPO officially became a part of collaboration structure. We also provide sample tools used for formative and summative assessment of various projects described in the article.

This includes content regarding:

1. DES Project and Science

2. Projects in Progress Before the Creation of the EPO Committee

3. Specific EPO Project Logic Models

4. Internal Survey for Formative Evaluation

DES Project and Science

In the late 1990s, two teams of astronomers made the unexpected discovery that the Universe is expanding at an accelerating rate (Perlmutter et al., 1999; Riess et al., 1998). The mysterious agent of this acceleration, which acts against gravity’s attractive force, has been named “dark energy.” Understanding the nature of dark energy has become one of the greatest unsolved problems in modern cosmology (Hinshaw et al., 2013; Planck Collaboration et al., 2016). The goal of the international DES collaboration is to study this accelerating expansion with unprecedented precision and accuracy.

DES is surveying 5000 deg2 of the southern sky, using the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) (Flaugher et al., 2015) mounted on the 4-m Victor M. Blanco telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile. DES is scheduled to take data for five years (2013-2018), observing each year from August-February. Although much of the observing is computer-automated, DES collaboration members travel to the telescope site during the DES season to help take data. Once DES data is collected, the DES Data Management team stores and processes the data, preparing it for DES scientists all over the world to analyze. DES traces its origins as a project concept back to at least 2004. However, the first DES images were not taken until September 2012.

One of the unique strengths of DES is that it employs four complementary techniques to study the effects of dark energy, through observations of: Type Ia supernovae; gravitational lensing; galaxy clusters; and baryon acoustic oscillations. During the course of the survey, DES will observe thousands of supernovae, map millions of galaxies, and measure the growth of large-scale structure of our universe (The Dark Energy Survey Collaboration, 2005).

In addition to studying fundamental cosmological probes, DES makes important contributions to astronomy. DES scientists study the outer reaches of our solar system, finding new candidates for dwarf planets (Gerdes et al., 2017) and other trans-Neptunian objects. They identify galactic neighbors to our Milky Way (Li et al., 2017). They search for optical counterparts to newly discovered gravitational waves (Abbott et al., 2016).

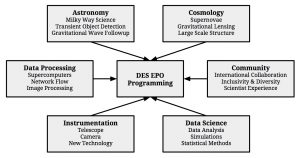

Fig. 2 Schematic diagram illustrating various components of DES which provide inspiration for the EPO effort. Examples included here are merely a subset.

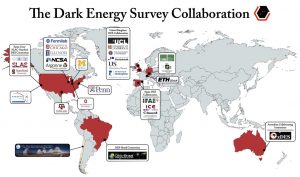

DES is a collaboration of over 500 scientists from 25 institutions in seven countries

around the world (Fig. 1). University faculty and researchers, laboratory and observatory staff scientists, postdoctoral researchers, graduate students, and undergraduates are all working to answer unanswered questions about our Universe. The support staff, at the telescope and at DES institutions, enable DES scientists to travel for observing and to gather to discuss latest results at conferences and collaboration meetings. Together, members of the DES collaboration are at the cutting-edge of science and forging a new frontier for large-scale astronomy.

The various aspects of the survey highlighted here are summarized in Fig. 2. The DES EPO program draws inspiration from each of these components to design innovative EPO programming without necessarily relying on published data products. Examples included in Fig. 2 represent only a subset of the material available for EPO programming.

Organization and Management

The three signatory institutions of DES are the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (hereafter Fermilab), National Center for Supercomputing Applications (hereafter NCSA), and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (hereafter NOAO). Support for DES is provided by grants from these respective institutions, primarily from the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation. Members of the DES Project Office report directly to these agencies.

DES Scientists are categorized into members, participants, and external collaborators.1 DES members are senior scientists, including faculty (tenured and tenure-track) and senior research associates, at official DES collaborating institutions. Participants are typically current postdoctoral researchers and graduates students of DES members. Members and participants have access to DES data and data products. External collaborators are senior scientists at non-DES institutions who provide resources that are otherwise unavailable to the collaboration, e.g., access to private telescopes. Participants can gain permanent access to DES data by working on DES infrastructure. Infrastructure activities include work on DES instrumentation, pipeline development, data calibration, and management activities. After one year of Full Time Equivalent (FTE) infrastructure work, participants can apply for data rights; after 2 FTE, participants can apply for Builder status, which includes data rights and optional authorship on DES papers. We will refer to our DES colleagues as “collaboration members.” This includes full DES members, participants, and external collaborators.

There are several channels available for DES scientists to communicate within working groups and across the collaboration. All scientists are encouraged to subscribe to a DES-wide LISTSERV (electronic mailing list) which is used for collaboration updates. Twice a month there are collaboration-wide telephone conferences where scientists can share results and receive feedback. Collaboration leadership also organizes two annual in-person week-long meetings where scientists congregate to discuss progress and results.

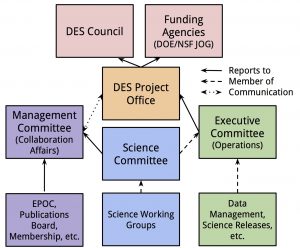

Fig. 3 DES internal organization chart, including the EPOC (purple), adapted from the DES director’s presentation at the Fall 2016 collaboration meeting. Solid arrows indicate a group that reports to and/or is appointed by the box to which it points. Dashed arrows indicate that the people named in that group are members of the higher-level Committee to which that box points (e.g., science working group coordinators are members of the Science Committee, and the Science Committee co-chairs are members of the Executive Committee). Dotted two-way arrows indicates a line of mutual communication.

The internal organization of DES is divided into three main components: collaboration affairs, science, and operations. Collaboration affairs are overseen by the Management Committee, who are responsible for making collaboration-wide decisions including membership and publication policy. The Science Committee is responsible for managing the DES scientific program and ensuring all science requirements are met. Telescope operations, data management, and science releases are overseen by the Executive Committee. Each of these three committees is further subdivided into a variety of smaller groups, e.g. the Science Committee is comprised of science working groups and the Management Committee oversees the Publications Board (who review DES publications and enforce DES publication policy) and Speakers’ Bureau (who recruit DES members to speak at conferences on behalf of the collaboration). Each subcommittee is governed by official protocol that dictates how collaboration members should work both within the respective committee, and with the collaboration as a whole.2

The DES Education & Public Outreach Committee (EPOC) became a part of the official DES organizational structure in the Fall of 2014 and was placed under the umbrella of collaboration affairs (for details regarding the creation and development of the EPOC, see The Evolution of the EPOC below). Prior to that time, DES did not have a centralized EPO effort nor official recognition of EPO on a collaboration-wide scale. As such, once the EPOC formed, there were no policies in place for how the EPOC and its programming should interact and coordinate with the rest of the collaboration. For example, representatives from the EPOC are not invited to Management Committee meetings, although other committees responsible for collaboration affairs are included. A summary of the current DES organizational structure, including the EPOC, is presented in Fig. 3.

The roles and responsibilities of the EPOC have evolved organically since its inception. As the primary organizers of EPO for the collaboration, the EPOC oversees and contributes to: updating and maintenance of the DES website, DES social media, creation of informal and formal educational materials, DES events with local communities (e.g., museum events and science fairs), internal EPO reporting, public relations,3 and much more. The centralized DES EPO program has a limited, floating budget per the discretion of the DES director, which is jointly funded by the DES collaborating institutions. Details of how these funds have been allocated thus far are discussed in the article.

The Evolution of the EPOC

Prior to the Fall 2014 collaboration meeting at the University of Sussex, no sessions dedicated to EPO had been scheduled by the scientific organizing committee (SOC). Kathy Romer (a faculty member at Sussex) was the chair of the Sussex SOC and decided to arrange two EPO sessions. This was done in consultation with Brian Nord (at the time, a postdoctoral researcher at Fermilab), who had been, by then, running a DES EPO initiative known as The Dark Energy Detectives blog (see Dark Energy Detectives below). Nord was not able to attend as he was observing in Chile, but recommended that Romer speak to Rachel Wolf (at the time, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania) about enhancing DES’s social media presence (Romer’s EPO focus to that date had been on working with school groups). And so began a grass-root effort to inspire coordinated EPO initiatives within DES. By the end of the Sussex collaboration meeting, Romer and Nord were asked by the DES director to lead an official EPO committee (the EPOC) for DES. They agreed to do so on the condition that Wolf was also included. Nord, Romer and Wolf (NRW hereafter) thus officially became the coordinators of the EPOC.

To discuss the organization and implementation necessary to get DES EPO off the ground, NRW established weekly (EPOC coordinator) telecons. NRW also created an internal DES EPO LISTSERV to communicate about EPO projects and opportunities with colleagues.

During the first year of the EPOC, most programming was organized and executed by NRW. Much of the effort was focused on updating, enhancing and maintaining the DES online presence. At the following semi-annual collaboration meeting (Spring 2015), NRW organized several EPO-specific sessions to present the work carried out so far, to receive feedback, and to generate new ideas. There were no shortage of new ideas and it became clear that more colleagues would need to be recruited to keep up with demand. Fortunately several DES members were eager to contribute, and even to lead, certain EPO projects, especially those that appealed to their particular interests (e.g., writing, artwork, or astrophotography). In addition to the weekly NRW coordinator meetings, monthly EPOC telecons were established to discuss the progress of the various projects. One of those projects is internal communication and resulted in a monthly DES-EPO newsletter that is sent electronically to every registered scientist in the DES membership database.

Projects in Progress Before the Creation of the EPOC

Dark Energy Detectives

One substantial EPO effort was in place before the formation of the EPOC in Fall 2014: Dark Energy Detectives (DED). This was a blog series, organized by one of the future founders of the EPOC, that used creative writing to tell stories related to the science, technology, and processes underpinning DES.

In each DED entry, the writer assumed the role of a detective or sleuth and described a mystery in which cosmology was the backdrop. The style was borrowed from film noir and emulated many works of cinema and fiction that have permeated pop culture over the last 40 years. Each post featured an image or video related to DES. This strategy was employed in an effort to reach audiences that had not previously engaged with science EPO. DED was published via Tumblr, and reached ∼45,000 Tumblr followers at peak popularity. It was supported by a dedicated Twitter account that also strictly maintained a film noir tone.

DED posts were made over the course of three DES observing seasons (August to February), with a bi-monthly cadence. During the first of these observing seasons, all of the posts were written and managed by a single individual and benefited from professional editorial assistance (from the Fermilab Communications’ Public Information Officer). Thereafter, an increasing fraction of the posts were written by guest authors (other DES scientists), with editorial assistance provided. Each piece required one to three weeks of writing and editing (albeit not full time), including correspondence between writer and editor. The prescribed narrative tone required close coordination between the editor and each writer.

After the formation of the EPOC, attention and resources switched focus from DED to providing support to other DES EPO activities. As a result DED was phased out after the end of the third observing season.

Discussion

By metrics of user reach, and the creative use of new media, DED was a successful DES EPO product. The DED project gave eager scientists the opportunity for creative writing. However, maintaining the film noir style amongst a community of writers (many of whom were unfamiliar with the genre) was difficult. Only a handful of DED posts were made after the formation of EPOC diverted volunteer time elsewhere. The project would have been more efficient and sustainable had it relied on just one or two dedicated writers with prior experience in science communication.

Take-Home Messages

Tumblr is an appropriate platform for long-form, blog-style EPO content (see the article for contrasting examples). It is best to target scientists who enjoy writing for the public (and who have prior experience) for long-form pieces, rather than trying to encouraging everyone in a collaboration/organization to take part. That said, it would be a good use of a collaboration’s/organization’s financial resources to provide training opportunities to all members; in doing so, scientists might discover a previously unrecognized enjoyment for, and/or talent in, science writing.

The DES Website

Before the creation of the EPOC, the DES website was not regularly updated or maintained. When the EPOC was founded in October 2014, NRW assumed the responsibility of updating the DES website. The aim was a modern, user-friendly, website with integrated social media.

Rather than update the content of the existing DES website, we decided to create a new website that would meet aesthetic, content, and user-interface goals. This involved updating the “back-end” data access structure as well as the “front-end” publicly accessible presentation layer. This process, from development to public launch, included: 1) seeking out an external web development agency and obtaining their advice, 2) designing the layout, user experience, and information content, 3) organizing the back-end features necessary for page updates and maintenance, 4) creating, reviewing, and formatting content, and 5) designing a strategy for website maintenance.

Key choices for the front-end revolved around the user experience. We believed that if this element was appealing, simple, and intuitive, the audience would be able to navigate easily to the online content, and want to return to it in the future. Our goal was to create a site that was easy to navigate, both on a computer and mobile device, for a variety of user groups (e.g., professional astronomers, educators, general public). After much internal discussion and research of existing science collaboration sites,4 we opted for a compromise between a multi-page, hierarchical structure and one with more modern media-driven features. This allowed us to create a bridge between the past and present of science collaboration web pages; appealing to self-identified science enthusiasts who were already used to exploring well-organized and curated sites and new audience members who might be attracted by creative content and the multimedia-oriented main page.

Implementation of these front-end features relied on an understanding of back-end development. For reasons related to budget and site maintenance, we elected to utilize an existing WordPress template service for the back-end of the new website. However, as the EPOC coordinators did not have the necessary web developing experience, we contracted a professional website development team to adjust the back-end structure to suit our needs. Funding for this project was approved by the DES director and was drawn from contributions from DES collaborating institutions. We worked with the development team for a year and a half and the cost ultimately came to ≈ $5000. This was the largest single-project budget of any of our other EPO programs and greater than the sum of EPO funding allocated for all other DES EPO projects.

Much of the developers’ time was spent organizing the back-end structure so that site maintenance would be straightforward. For example, they created a slide interface for easy graphic uploading and multiple web forms for adding new content. Once the website was publicly launched, updating and adding content and other site maintenance was under the purview of the EPOC. Much of the content for the new site was transferred from the old; however, we devoted a substantial amount of time to updating and rewriting sections on a range of topics from DES science to collaboration structure. Most of the time from the EPOC went toward creating an interface that was navigable by both new and returning visitors, and relatively extensible, should we find a need for new sections of content.

The second and third phases took place concurrently and took ∼6 months to complete (not because they were particularly big tasks, but because they had to fit in with our primary responsibilities, such as research, teaching etc.). Converting and developing new content slightly overlapped with the earlier design phases and required ∼3 months to complete.

Although we believe the current DES web page is a significant improvement from the previous public page, development and maintenance required much more time and effort than we anticipated. In hindsight, we believe we devoted too much time to designing and creating the optimal aesthetic. This allocation of resources meant that we then did not have enough time to create and review static web page content or develop other EPO projects. In fact, several pages of written content had not been published (at the time of writing) because we lacked resources for editing. In addition, social media platforms have been taking up larger sections of the online landscape. These social media platforms house content and can provide gateways to an organization’s website; in this paradigm, websites are most useful when they provide interactions and content that are not readily available through a social media platform. We believe that is the scenario in which content-driven science websites are most likely to be visited.

Take-Home Messages

A well-designed and well-maintained website is an invaluable resource for both the public and for members of the respective collaboration/organization. We strongly recommend other large collaborations/organizations planning EPO science programs devote whatever resources possible to contracting an external web development team who can lead back-end development and aesthetic design. By doing so, the time that volunteers can contribute can be used for writing scientific content. In our experience, the best way to generate content collectively is via “hack sessions” at collaboration meetings (emails requesting content from individuals did not usually deliver results). Finally we stress the importance of providing versions of the website in other (than English) languages (see Section 3.7 of the article).

Image & Video Curation and Creation

Images and figures are a vital component of DES science and DES EPO, and are used for science communication both within the scientific community and with the public. Before the creation of the EPOC, there was no collaboration standard for media creation or curation. As part of the goal to centralize DES EPO efforts and products, we attempted to consolidate image management for the collaboration as a whole. This was more successful for some types of images than others. In this section we discuss the creation and curation of four main types of images: 1) figures that appear in DES publications and talks, 2) false-color DECam (astronomy) images, 3) photographs and simple videos, 4) astrophotography, infographics, and edited videos.

Project Organization and Implementation

Figures that appear in DES publications and talks – Any publicly-released DES material (e.g., figures, refereed journal articles, or DES-approved conference presentations) can be used by DES members for other purposes, including: talks or presentations (for fellow astronomers/scientists or for the general public), popular science articles, or social media posts. To ease the process of accessing figures approved for public dissemination, the DES Publication Board created a central Figure Library. This is a password protected-database of selected plots and accompanying descriptions; descriptions are written for DES members who are not experts in the relevant subfield. The collaboration was initially slow to adopt the Figure Library. However, after its use became part of the official DES publication policy, compliance has increased significantly. By April 2017, the DES Figure Library had become a useful resource for DES EPO.

False-Color DECam Images – False-color5 images of astronomical objects are vital for effective communication to the public. This is best demonstrated by the huge popularity of the images in the Hubble Space Telescope gallery. For many years, the DES data management (DESDM) team did not prioritize the development of software to generate these high quality-images (which are not often necessary for scientific analyses). Instead, DESDM primarily devoted their limited resources to creating the source catalogs necessary for DES science. To fill the gap, a handful of collaboration-member teams unilaterally developed their own software for false-color image generation. These teams were largely motivated by the needs of their scientific research, but some were instead (or also) motivated by EPO goals. All of these efforts were well-intentioned, but there was significant overlap and duplication. The resulting lack of cohesion, especially with regard to agreed quality standards, meant that the EPOC was not able to fully exploit the vast wealth of DES image data.

Photographs and Simple Videos – The reach and impact of the online initiatives was significantly enhanced when pictures or other visual media were included. The DES EPO program was fortunate that it did not rely on choreographed “photo-ops” or professional photographs. Rather, we capitalized on the fact that collaboration members like to take, and share, photographs and videos related to their science experience (e.g., from DES observing trips, DES collaboration meetings, or working group meetings). The DES EPOC regularly encouraged members to share their images, which were then archived using a private Flickr repository. Meta-data, including photographer name, image location, and photograph date, were collected with the images. Given that an individual member may generate hundreds of photographs during a single observing shift, we selected a small sample of images to embed on the DES website. Videos embedded on the website were selected in a similar fashion; additional video material is shared via the DES Youtube channel. Collaboration members who contributed visual media were encouraged to sign a Creative Commons agreement, as this eased the process of distribution to outside media sources (e.g., local newspapers). The DES Flickr and YouTube accounts were maintained by DES members on a voluntary basis.

Astrophotography, Infographics and Edited Videos – Advances in technology have enabled professionals and amateurs alike to capture pictures and videos of the night sky. However, it requires technical skill, and expensive equipment, to produce astrophotography images and videos.6 The production of time-lapse videos and images from these photographs is also technically difficult and time consuming. Astrophotography images and videos were of particular value to DES EPO, as they capture the public’s imagination in a way that even false-color DECam images cannot.

Infographics7 are another genre of image that were integrated into DES EPO. Infographics can be static, moving (i.e., animated .gif format), and/or interactive. Com- pared to snapshot photographs, creating infographics requires more technical complexity, design considerations, and knowledge of the target audience. The DES EPOC commissioned (from volunteer members) a handful of infographics. For example, we en- listed volunteers to create an interactive world map showing the global distribution of DES members’ host nations; this was useful not only for internal membership, but for media searching for scientists in their local communities. We also curated infographics developed by DES institutions for press releases or by individual DES members for their personal social media accounts.

Edited videos were the most difficult and costly (in terms of members’ time) visual media to produce. The DES EPOC commissioned (from volunteer members) a handful of such videos. We also curated edited videos developed by DES institutions to accompany press releases. Astrophotography, infographics and edited videos that were provided to the DES EPOC by DES members were archived and shared in the same way as simple photographs and videos (see above).

Discussion

Figures that appear in DES publications and talks – The DES Figure Library was developed after the formation of, and without consultation with, the DES EPOC. The lack of consultation, and the fact that the DES membership were originally resistant to the concept of a Figure Library, was for a while problematic for DES EPO. For example, the lack of compliance with the Figure Library meant that EPOC volunteers needed to extract figures from certain papers themselves to ensure the DES website publication pages were kept up-to-date.

False-Color DECam Images – Had the production of such images been prioritized by DES management, it could have been easy to have added a “DES Picture of the Day”8 component to our online EPO portfolio.

Photographs and Simple Videos – In hindsight, we should have dedicate more resources (in terms of volunteer time) to the collection and curation of these types of data. There are thousands of member-produced images that have not yet to be loaded into the Flikr repository. There were also several occasions when the media contacted DES asking to publish images and we were unable to work quickly enough to meet their requests, especially with regard to strict requirements on copyright.

Astrophotography, Infographics and Edited Videos – The EPOC would have liked to have commissioned much more of this type of material, but this was not possible given the limited financial resources available.

Take-Home Messages

Media in the form of properly curated false-color DECam images, analysis figures, photographs, and videos are one of the most important legacy components of large scientific collaborations. However, in DES we have yet to fully exploit our potential to deliver interesting, eye-catching, and educational media. This is partly due to lack of resources, and partly due to lack of planning. We recommend that future large science projects design an image organization scheme early on and advertise image and video repository structure clearly and consistently. In hindsight, we should have put more time into the curation of DES members’ photography. Much of that curation work could be done by undergraduate “work-study” students, and we encourage other collaborations/organizations to set aside a small financial sum to cover that type of work. We conclude that a centralized Figure Library to archive science figures from publications can be worthwhile, but that it needs to be included in a publication policy sequence from the outset to ensure compliance. Finally, and in the particular case of large-scale astronomy projects, we stress the need to generate eye-catching false-color images, and recommend that resources (including financial) are allocated, and quality standards agreed, centrally from the outset.

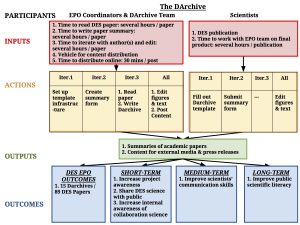

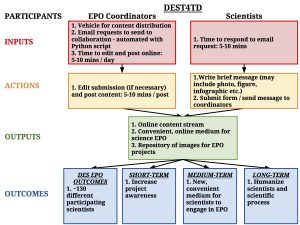

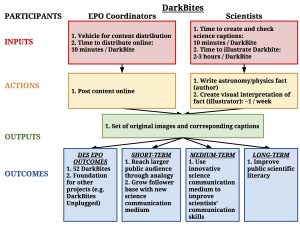

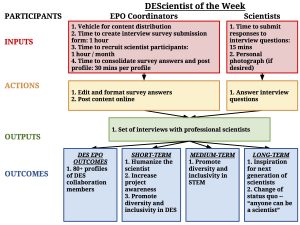

Specific EPO Project Logic Models

Here we present logic models for The DArchive, DEST4TD, DarkBites, and DEScientist of the Week EPO initiatives (as described in the article). In each model, we describe the inputs, actions, and product outputs created by the EPOC coordinators and participating scientists. We also present the DES-specific outcomes, as well as the predicted short-term, medium-term, and long-term outcomes. We encourage readers to treat these logic models as planning outlines for the respective projects and leave details on project evaluation for a future publication.

Internal Survey for Formative Evaluation

Approximately one year after the formation of the EPOC, we conducted a survey to gauge collaboration members’ awareness of and attitudes towards the DES EPO program in general as well as four specific EPO initiatives. We created an online survey and emailed it to the entire collaboration, asking all collaboration members to participate. We also advertised the survey at the Fall 2015 collaboration meeting. DES stickers were offered to those who participated in the survey. A total of 90 collaboration members participated.

For a transcribed copy of the survey, click here. Asterisks indicate questions which required a response. Participants were offered the opportunity to exit the survey after a few key sections; these are indicated with investigator notes. The online version of the survey included examples of the particular EPO initiatives for those who indicated they were unfamiliar with a particular project. We do not include these examples here. We note that personal identifiers were not used in survey response analysis.

Contributions to the Article

Here we outline specific contributions to the writing of the article.

Design, writing, and correspondence

R. C. Wolf is responsible for the overall article design and the majority of the writing. Wolf provided analysis and is the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting writing and analysis

A. K. Romer and B. Nord provided insight regarding the organization and writing of specific sections, in particular for those related to projects in which they had unique knowledge or experience. As an EPO and communications professional, L. Biron provided valuable perspective and feedback. K. Bechtol and J. Zuntz provided valuable feedback during the writing process as internal reviewers.

Data acquisition

A. Ferté gathered social media analytics data and J. M. Hislop obtained internal assessment data.

Contributions to Online DES EPO

Here we provide a breakdown of major contributions to the online DES EPO initiatives, without which the work described in this article would not be possible.

Social Media Management

R. C. Wolf provided essential effort in maintaining consistent social media output for three years.

Dark Energy Detectives

Many DES Scientists contributed articles to this effort. B. Nord edited and provided content, and originated the concept and design.

Web Site

Kevin Munday, Carolina Manel, and Xenomedia were paid for their work to build the DES Web Site. B. Nord led the design and content development.

The DArchive

(See Section 3.1 of the article for more information)

The DArchive originated when R. Cawthon, B. Nord, and R. C. Wolf sought a method to convey DES papers more directly to the public. Editing, writing, and organizing was performed by R. Cawthon, R. C. Wolf, A. Kremin, M. S. S. Gill, B. Nord, and A. K. Romer. Many DES scientists contributed content and time.

DEST4TD

(See Section 3.2 of the article for more information)

A. K. Romer and R. C. Wolf were the principals for designing and organizing this initiative to bring consistent connection between scientists and the public. T. Lingard wrote code to automate scientist recruitment. J. M. Hislop subsequently developed and maintained the code. Many DES scientists contributed content.

DarkBites

(See Section 3.3 of the article for more information)

The content of this program was made possible by C. Chang, D. Q. Nagasawa, R. R. Gupta, J. Muir, and E. Suchyta. B. Nord originated the concept, based on an observations of how some science communicators successfully approach social media interactions.

DEScientist of the Week

(See Section 3.4 of the article for more information)

R. C. Wolf initiated and carried out this effort to humanize scientists and normalize the science profession in broader culture.

Multilingual EPO

(See Section 3.5 of the article for more information)

The MLDES project would not have been possible without the many collaboration members who volunteered their time to translate various social media posts (including DEST4TD and DarkBites). S. Avila, A. Möller, A. A. Plazas, and I. Sevilla-Noarbe were primarily responsible for translating content for the Spanish-language version of the website. T. S. Li and Y. Zhang translated content and managed the DES Weibo account.

Image Curation

S. Hamilton and R. Das lead the effort for DES image curation and management. This included DES science images, as well as other photographs, slides, and images that could be used for EPO activities.

YouTube and other Visual Media

The DES Youtube channel and other visual media have primarily been managed by C. Krawiec.

References

The Dark Energy Survey Collaboration. (2005, October). The Dark Energy Survey. astro-ph/0510346 .

1DES membership policies and infrastructure tasks are described in the DES Membership Policy. [Back to text]

2Further detail on DES policies and organization can be found in the DES Memorandum of Understanding. [Back to text]

3Note that this is distinct from official press releases which are organized through the Fermilab press office. [Back to text]

4E.g., hubblesite.org and sdss.org [Back to text]

5All astronomy images taken by CCDs are gray scale. However, if several images are made of the same patch of sky through different filters, then it is possible reconstruct a color image using software. [Back to text]

6Astrophotography is a subdiscipline in amateur astronomy that seeks to produce aesthetically pleasing images rather than scientific data. [Back to text]

7Graphic visual representations of information, data or knowledge intended to present information quickly and clearly. [Back to text]

8Along the lines of the hugely popular Astronomy Picture of the Day initiative. [Back to text]